What I Learned Running This Heist TTRPG for One-Shots

My experience with The Job, a game about planning and executing extravagant heists.

I’m Colin, and I’m a professional video game designer. This is Drolleries, where I write about d&d, ttrpgs, and game design.

I tried to run a heist in 5e, but it didn’t feel like a heist.

It felt slow and tedious. The pace of everything skidded to an abrupt halt once the players started fighting the guards. Even using the Alexandrian’s raid structure to abstract distinct rooms into general areas, actually exploring the bank vault was boring and didn’t move the story forward fast enough. This heist took 4 sessions (that’s about 16 hours) to resolve. It might have still been cool for 5e, but it didn’t fill the heist-shaped hole in my heart.

Since then, I had been seeking redemption. I wanted to run a heist that actually felt like a heist. Fast and dangerous, without hand-waving the specifics of the plan.

I finally found redemption with The Job.

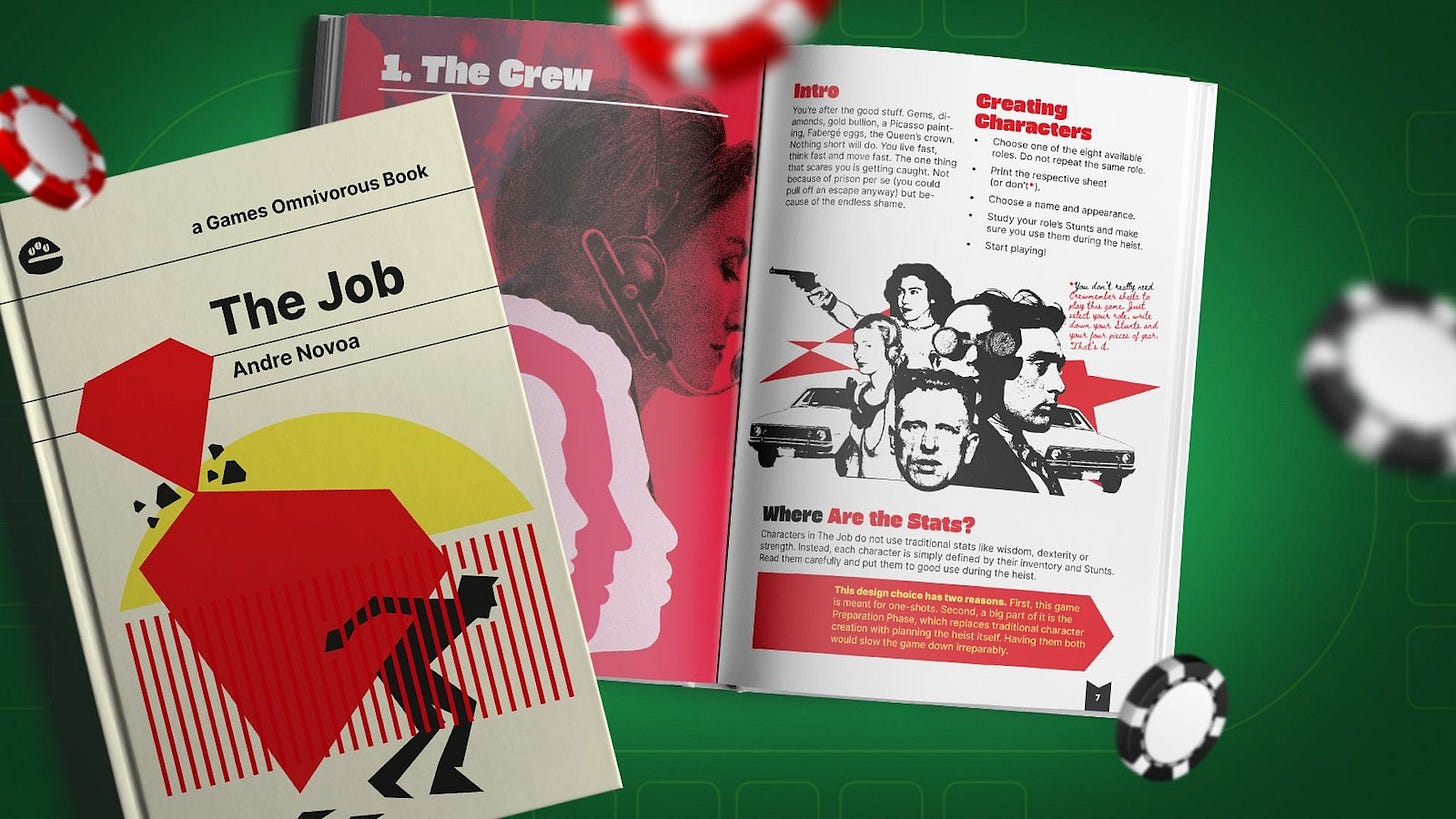

The Job is a one-shot heist ttrpg by Andre Novoa and Games Omnivorous (the indie publisher behind Mausritter and Vaults of Vaarn). It’s bursting with stylish art and sarcastic dialogue, drawing from classic heist movies.

Given the modern setting, simple mechanics, and flavorful classes that take obvious inspiration from classic heist movies, this game is great for players who are new to ttrpgs. New players love leaning into the known cliches, so fantasy games like d&d can feel foreign to someone unfamiliar with the tropes. But everyone knows Ocean’s Eleven, or Baby Driver, or Thief — heist movies have been ubiquitous in pop culture for decades.

The Job is also cinematic in a literal way - it encourages the GM to run the game as a director, framing everything in terms of scenes and setbacks. I loved this, and it changed the way I run games.

Here’s what The Job taught me about GMing.

The Core Roll

In The Job, when you attempt a particularly complicated action in order to overcome a challenge of the heist, you roll 2d6.

On a 2-6, the action fails. Add dice to the stack.

On a 7-9, the action succeeds, but you choose between adding dice to the stack OR taking a setback, which the GM can introduce later.

On a 10+, the action succeeds, and you can remove one die from the stack.

When you use your class-specific abilities or the appropriate gear, you get advantage and can roll 3d6 and drop the worst result. With disadvantage, you roll 3d6 and drop the best result.

Importantly, there’s no stats. At a base level, everyone is equally competent at everything. The differentiation between classes comes purely from their abilities.

That means no math!

Well, you do have to add the dice together, but there’s no floating modifiers, no changing target numbers, and no counting up damage or subtracting from hit points.

The simplicity of this resolution mechanic really shines in The Job. It’s lightning-fast and focused on the fiction. Once the dice are rolled, everyone reacts immediately with either excitement or worry. Also, because time is already spent adding or removing dice from the stack, it’s fitting that there’s no additional math to slow things down.

That brings me to my favorite part of this game — stacking dice.

Stacking Dice and Choosing Setbacks

The dice stacking is inspired by Dread, a horror ttrpg that uses a Jenga tower as its core resolution mechanic. In Dread, you pull a block for each action, and if the tower falls over, your character dies or worse (possessed, paralyzed, runs for their life, turns on their friends, etc.). It’s super effective at creating a feeling of… well, dread. As the tower gets more and more unstable, the players’ fear in the room rises, and they’ll do anything to avoid pulling a block, which encourages them to run from the monster rather than try to face it head-on.

Similarly, in The Job, the stacking of dice creates a feeling of tension and worry that permeates the entire game. It’s not just when a player goes to place another die on top of the stack. The feeling that a wobbly dice tower creates pervades all moments of the game.

Looking at a wobbly dice tower, the players start to doubt their plan. They measure its wobbliness against how many scenes they know are left in their plan. If we keep stacking dice like we’ve been doing, it’s definitely going to fall. We have to try to get advantage, does anyone have more gear they can use? Anyone have any abilities they can use? Okay, everyone stop stacking dice! We have to choose setbacks, otherwise the tower’s going to fall.

These are all thoughts my players verbalized. And they’re exactly the type of thoughts that should influence their decisions during a high-stakes heist.

The dice stacking also accelerates. Each time the tower falls, the players must place one more die on the tower. So the first tower is built one die at a time, but for the second tower, the players must stack two at a time, and so on. The third tower goes up really fast, and if it falls, the players fail the heist.

This acceleration also creates that feeling of everything getting really bad really quickly. Even if the players are “ahead” of the curve, either by luck or skillful stacking, after just one failure, the story can change really quickly.

This means that early in the night, the players can effectively ignore the consequences of rolling poorly by stacking dice with impunity — everything’s going according to plan. But later in the heist, as the height of the tower and the difficulty of stacking both increase, players start choosing to let the GM introduce setbacks. Because the players are forced to stack dice on a roll of 6 or below, if the tower is already too tall, it’ll be too late to avoid their fate. It’s a risk-reward assessment where players gamble against their future selves.

It’s a really interesting choice, informed by both the current height of the tower and the fiction of what the player was attempting to do. Both options make things harder, but it’s the player’s choice how. Depending on the fiction of what the player’s attempting, it can be obvious how bad a setback would be. Everyone at the table can imagine how a setback on hacking the security cameras can be really bad for them later on.

But the current height of the tower also changes. When the tower is small, players are more willing to choose to stack dice, but when the tower looks wobbly, players are more likely to accept a setback. And because the tower rises and falls 3 times throughout the night, the player’s heuristics are are always changing.

The rising and falling of the tower also influences players to not choose setbacks too many times in a row. When the tower is tall and the players are most likely to choose setbacks to avoid stacking, eventually a roll of 6 or below will force players to stack dice and topple the tower. Then it’ll usually be a while before players start imposing setbacks again.

Incorporating Setbacks

In my last article, I talked about how partial successes can be difficult to run for the GM, both in terms of balancing the power of consequences and the difficulty of improvising on the spot.

But The Job fixes both of these issues.

Setbacks are explicitly meant to be introduced later in the story. As opposed to the GM having to improvise something on the spot, the GM is told to use setbacks in future scenes when it’s appropriate. For example, if a player takes a setback while trying to disguise themself as a guard, nothing happens immediately. The GM can just say “the guard looks at you skeptically, but lets you pass.” Then, in a later scene, when it’s dramatically appropriate, the GM can have a guard come running in with reinforcements — “That’s him! He’s wearing Ted’s uniform!”

Also, because the players choose to introduce setbacks, and they’re not too common, I felt free as the GM to make the setbacks consequential. They didn’t happen every time, so I could go big and introduce major twists that complicate their plans. The worse a setback is, the more tempting it is to stack dice instead.

Planning the Heist

The Job is also explicitly cinematic, and makes the GM into more of a Director.

The first half of the session is the planning phase, where the players come up with a list of scenes that explain how the players overcome the specific obstacles of the heist. It’s comparable to how a writer would outline an actual story, where each scene is framed around a dramatic question. Can the Boss fast-talk his way past security and smuggle in his weapons? Can the Genius hack the security cameras without anyone noticing? Can the Greaseman drop in through the vents and steal the crown during the brief period of lights-out?

This was really fun for my group, but it was a bit chaotic. I had a lot of players (7 if I remember!), so it took a bit of wrangling to get everyone to agree on a plan. But that’s part of the heist genre — planning is part of the fun!

The process of outlining scenes also created a sort of balance, regardless of how outlandish the players’ plan is. Because the outline creates a number of scenes, and the GM is advised to call for a certain number of rolls per scene, as long as every obstacle is addressed in the outline, most plans have about the same chance of success. Good plans still matter, but there’s a baseline level of how difficult the plan can be to execute. Combined with the ridiculously bombastic class abilities, this encourages the players to concoct outrageous plans that feel huge and cinematic as opposed to defaulting to a plan that’s boring and safe.

Framing Scenes Strongly

There’s a piece of screenwriting advice that says “Enter the scene as late into the action as possible, and leave the scene as soon as you can.” It’s meant to encourage writers to skip the boring stuff and only write the stuff that creates drama.

The Job embodies this mantra.

Like in a movie, scenes in The Job start when a player first encounters an obstacle, and they end once the obstacle is dealt with. The scene only goes on for as long as it has tension.

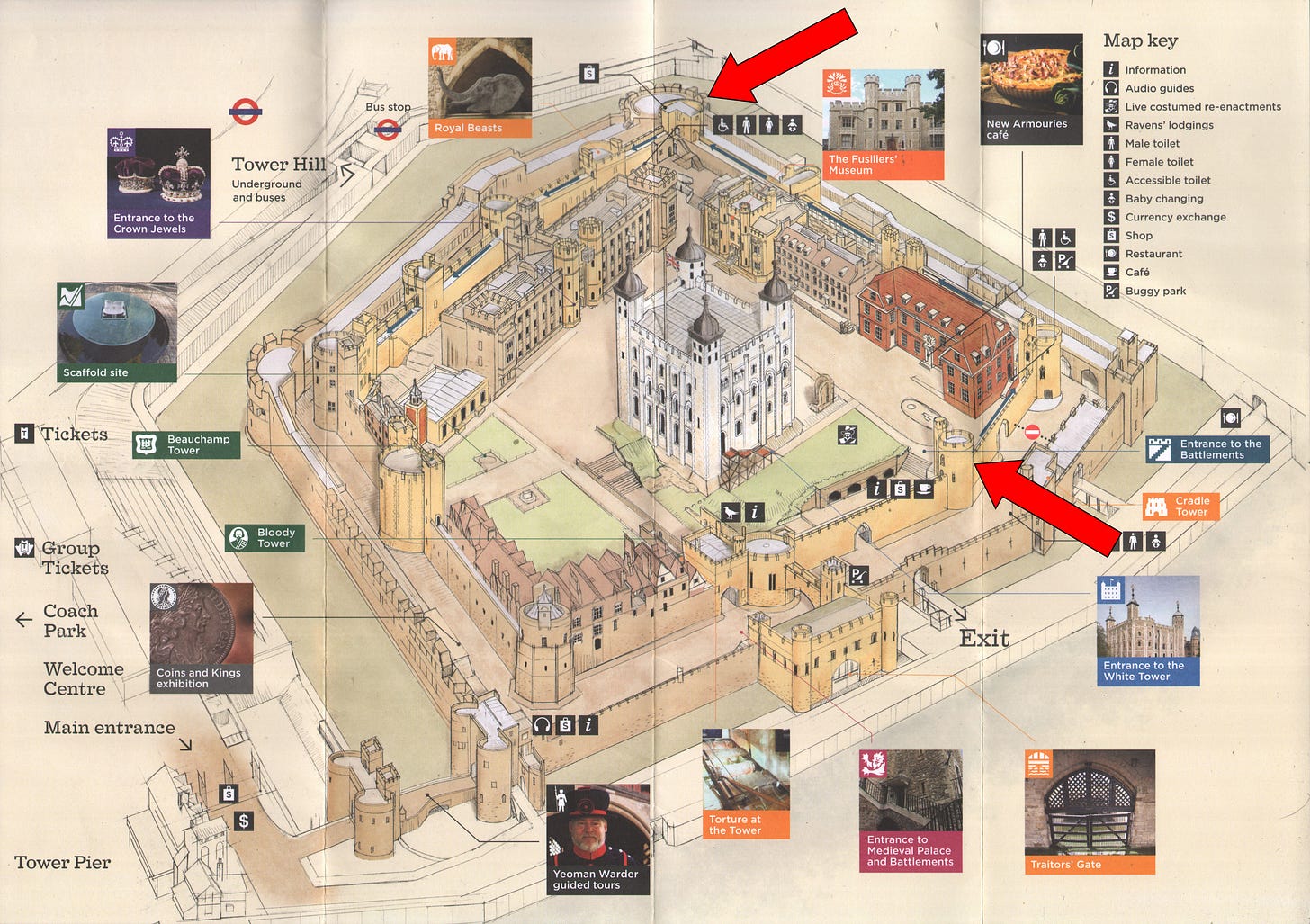

We don’t describe how the players navigate the hallways to get to the next obstacle, we just assume they can get to wherever the next important part is. We only spend time focusing on the important bits - skip straight from the security checkpoint to the room with the crown jewels.

It’s a basic principle of writing, but it’s not always true in running ttrpgs. Much time in d&d games is spent on the time in between encounters, counting travel days, describing environments, and shopping. The mere existence of the “shopping session,” where the entire time is spent roleplaying how the players spend their gold on equipment and magic items, exists in contrary to this principle. But heists are wall-to-wall action, so The Job makes sure that scenes never overstay their welcome.

Hard-framing scenes like this is good practice for GMs everywhere who want to run a more cinematic game, and it’s something that I took away from this experience. To hard frame scenes, you have to understand the players’ intent, then cut to when their intent meets resistance.

If it wasn’t already obvious, it’s important to mention that this is a choice of style. There is no right way to GM, and roleplaying games vary wildly in tone and genre. This advice is only useful if you want to run a game that feels more cinematic. Cutting straight to the action and skipping the day-in-the-life things like shopping and eating will make your story happen faster. But cutting the “boring parts” may also cut out the parts that immerse them in their characters and the world.

Thanks for reading! Let me know if you play The Job, I just hope more people find this awesome game.

Love the sound of this game, it'll have to go on my list! I particularly like the sound of the stack and the tension it creates.

Cutting straight to the action sounds fun too - did it feel railroady at all? That's always my fear when I want to jump to the exciting stuff!