Out With the Action Economy

Throwing out initiative and designing a narrative-first combat system for my heroic fantasy ttrpg

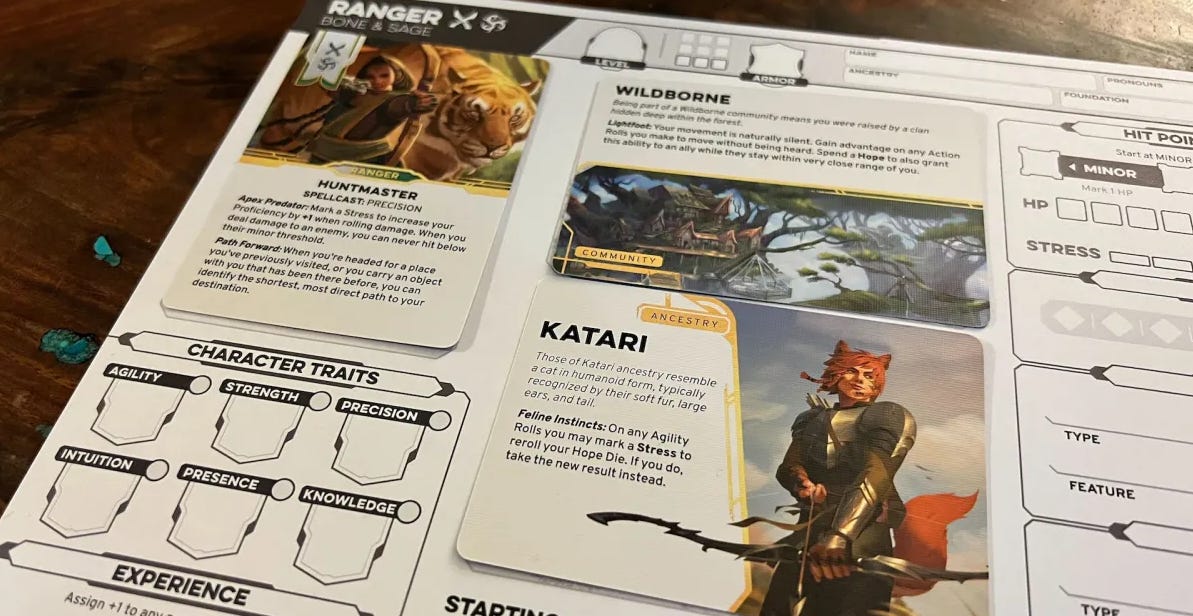

After I ran combat in Daggerheart, I couldn’t go back to tracking initiative.

In Daggerheart, there is no initiative, no turn order. Any player is free to take any action in combat, but if they fail an attack roll or roll with Fear, it becomes the GM’s turn. On the GM’s turn, they can activate monsters loosely based on how many actions the players have taken.

It feels fluid and natural. My players were engaged, constantly discussing tactics of who should act next, and nobody was scrolling on their phone waiting 15 minutes for their next turn. It also made combat much faster, because nobody took their turn until they knew what they wanted to do. And as the GM, I could follow the narrative, activating the monsters that would create the most drama and be the most tactical, instead of just the one who hadn’t acted the longest.

So when I sat down to design my heroic fantasy ttrpg, I was inspired by Daggerheart to ditch the initiative order and take a more narrative-first approach.

I’m Colin, and I’m a professional video game designer. This is Drolleries, where I write about d&d, ttrpgs, and game design.

The Action Economy Does Not Prioritize the Narrative

Legendary ttrpg designer Monte Cook spells out this issue with traditional initiative systems in his article Taking Turns, using the language of cinema.

Think about an exciting scene with multiple characters in a movie. The actions of the characters are rarely portrayed the way they are in an RPG. We don’t see Jack do a thing, and then Lucia do a thing, and then Kalisha do a thing, and then back to Jack doing a thing, etc. Instead, we see Jack jump off the moving truck, land in a dumpster, climb out, recover from all that, and then run into the burning building. Then the movie cuts to Lucia, who leans out of the window of the building holding a young child, dropping the kid safely down into the net held by Kalisha and her friend Emil. Kalisha grabs the child in her arms and carries them to safety across the street while Emil shouts up to Lucia to ask if anyone else is in the burning building. Lucia responds by saying she’ll make one last check.

That’s a very fluid set of events, but it doesn’t break down like most games would. Instead, Jack arguably does five things, Lucia then does one thing, Kalisha and Emil do an action together, and then Kalisha does another on her own. And then, rather than jumping back to Jack, we go to Emil and Lucia. Basically, the game isn’t dividing events into actions, but rather a variable series of actions, effectively completing a brief arc of what a character does. Everyone’s turn is their time to try to accomplish something satisfying and significant.

The reason why Jack cannot do five things while Lucia does one is because of the action economy. The action economy is the idea that each round, every combatant gets a turn, and on their turn they can perform 1 action. This system ensures fairness and predictability, at the cost of the narrative flow of the scene.

D&D inherited this system of the action economy from wargames, where the goal is creating an accurate simulation of combat. On my turn, all my troops get to move and attack, then on your turn, all your troops get to move and attack. If my army outnumbers your army by 16 troops, I expect that I will get 16 additional attacks than you. Numbers are everything: if you are outnumbered in an action economy system, you are at a severe disadvantage. Simulationism and realism is the most important factor.

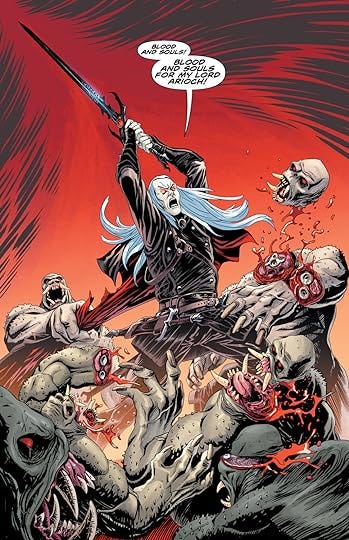

But that’s not how heroic fantasy stories work. Elric frequently takes on hordes of enemies, and it’s not because his GM decided all of them were 1-hp minions, it’s because the number of enemies isn’t nearly as important as their power. What most often determines the outcome of these fights is Elric’s position in the fiction: whether he’s injured, weak, empowered, or enraged. But if he’s outnumbered, that’s a key part of the fiction, and it’s a big deal and it’s obvious. Elric isn’t outnumbered facing 2 people, he’s outnumbered facing 50.

I’ll come back to this “outnumbered” idea later, with my system of the upper hand.

Crown and Skull: Variable Attack Power

Crown and Skull is a fantasy ttrpg by Runehammer with an interesting approach to running enemies in combat. Here’s a great video about it by Bob World Builder.

Each time an enemy acts in combat, the GM rolls 1d6 to decide what they will do. Here’s part of the entry for skeletons:

SKELETON (magically animated human remains, often armed)

Tactic 1: Stumble about, seek a new target

Tactic 2-5: Skeletons use rotten weapons, such as iron spears or rusty scimitars from ages past. Basic attrition

Tactic 6: Cleave attack! The skeleton builds enough strength to swipe its weapon at up to 3 foes in one strike with basic attrition.

The dice randomly generate the monster’s attack power. Each time a skeleton acts, there’s a 1/6 chance it moves, 4/6 chance it does a basic attack, and 1/6 chance it does a heavy attack. This allows monsters to have powerful attacks that are limited by their rarity, rather than GMs having to track spell slots or limited-use abilities. It’s similar to recharge abilities in 5e, but used for all enemies, and with less to track.

This inspired me, but because it’s purely random, the GM doesn’t have a choice to make. The GM can’t make tactical choices, or put pressure on certain player characters, or direct the narrative in a certain way. They just roll the dice and follow the statblock’s instructions.

What if instead of rolling for attack power per enemy, the GM rolled for attack power each turn, and could use that attack power on whichever enemy they wanted?

DOOM!

Here’s how combat currently works in my heroic fantasy ttrpg.

On the players’ turn, players generate doom by taking actions. A maneuver generates 1 doom (ex. moving one range increment, standing up from prone, or activating a minor buff). An action generates 2 doom (ex. a non-damaging spell or attempting a grapple).

After a player attacks, it becomes the GM’s turn, and the GM gains doom dependent on the result.

Miss: +6 doom

Hit: +3 doom

Critical Hit: +0 doom, and player turn continues.

On the GM’s turn, the GM spends doom to have enemies act. It costs about 3 doom to deal 1 damage.

In this system, a skeleton statblock might look like this.

Skeleton. Stamina: 1, Defense: 12

Move. 1 doom per close distance.

Basic Strike (3 doom). Melee attack. 1 damage.

Exploding Ward (4 doom). A symbol on the skeleton’s forehead glows before it explodes, killing itself and dealing 1 damage to all adjacent creatures.

Cleave (6 doom). Melee attack, 2 targets. 1 damage.

A big difference between this system and Crown and Skull is that the outcome of the player’s attack determines the power of the GM’s next turn. This is because if it was purely random, it creates the possibility of a “null result,” where the players miss, then the GM “misses” by not having enough doom to do anything, then the players could miss again. This is possible in 5e, and it’s boring - it only drags the combat on longer, and doesn’t push the narrative forward.

In this system, because the GM gets more doom if players miss their attack, the game state is always changing, which reflects what we imagine would happen in the fiction.

An Alternative to the Action Economy

Instead of an action being the unit for measuring value in combat, doom measures the heroes’ effectiveness each turn. This means that Monte Cook’s example could take place in this system, because players can take as many actions as they want, and the game only cuts away when they make an attack.

This system also creates a couple of important dynamics that make the game feel more heroic.

Fights don’t get easier over time. Even once you’ve reduced the number of enemies, the GM is still spending the same amount of doom, just on fewer enemies. It makes sure that each battle ends with a dramatic conclusion, instead of how in 5e and other action-economy-based games, once there’s 1 or 2 enemies left and the players know they’ll win trivially easily, the battle just becomes a slog to play out.

There’s no death spiral. A corollary to the first point, this means that if a player dies or is otherwise taken out of the battle, the players aren’t at a huge disadvantage. The math of the battle remains the same, and the only disadvantage the players have is not being able to use the dead character’s abilities. This means that fights can be deadly and dangerous without suffering the risk of a total party kill. In 5e, because of the action economy, even one player character dying can seriously risk the entire party losing the battle.

Faster GM turns. The GM doesn’t roll to hit, they simply spend doom in exchange for automatic damage. This means GM turns are more of a resource management game (similar to a board game like Arkham Horror). This means that the GM doesn’t have to spend time rolling to hit, doing math, comparing to a player’s AC, then rolling damage, doing more math, and announcing the total, as well as resolving player’s reactions to impose disadvantage, reduce the damage, or negate other effects. All that time spent executing the GM’s intent is eliminated. When a GM decides to do something, they just spend the resources and it happens. The GM decides to spend 3 doom, then says “The skeleton attacks you for 1 damage.” I think this is better because I want to spend the most amount of time on the player’s actions, rather than taking up too much “screentime” with the GM resolving the enemies’ actions, which feels to me like the equivalent of Netflix buffering.

Being Outnumbered - Upper Hand

As I mentioned before with the Elric example, being “outnumbered” can still be an important part of the narrative, even without the action economy. In my system, I call this the upper hand, and either you or the enemies can have the upper hand based on a number of factors. Here’s the rule:

In combat, determine who has the upper hand based on three factors: surprise, numbers, and power. If a side wins more factors than the other, they have the upper hand.

Surprise: Whichever side surprises the other wins this factor for the first round of combat.

Numbers: If one side has 3 more combatants than the other, they win this factor. Boss enemies cannot be outnumbered. GM has final say.

Power: Whichever side has the highest level combatant wins this factor.

When the GM turn starts, they gain doom based on who has the upper hand.

Players have upper hand: +0 doom

Neither: +1 doom

Enemies have upper hand: +2 doom

Putting it all together, I’ve playtested this system with my group and they loved the core idea. There’s still details to be worked out in terms of how much doom certain actions generate, how much doom the GM spends to do damage, and the relative value of player attacks, but the core system worked pretty well to create some really interesting and dramatic fights when they might’ve fallen flat with 5e.

We played a fight where the players fought 2 cultists and it stayed interesting and tense, even though the 4 players would’ve easily swept the floor with them in 5e if I didn’t give them an unreasonable number of hit points. This test was all the encouragement I needed to throw out the action economy for good.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe to hear more about the heroic fantasy ttrpg I’m developing!

This sounds really cool. I disagree with quite a few things you’ve written, but I really appreciate what you’re going for. I don’t know that it works as well for games with wound systems, but perhaps it could. I’ll experiment a bit.

Things I probably don’t agree with: turns are for fairness and structure. Not realism or simulationism. I can’t stand 5e, and it’s incredibly slow and leads to people on their phones. 2e doesn’t. So, some of the issues are the results of a bad action economy. Not of an action economy, full stop.